Week 2 Outline: Python Intro and Text Manipulation

Note: For this class we’ll start by using Python’s read-eval-print loop (REPL) and then move on to Jupyter notebooks.

Open Terminal in macOS and launch our Docker container:

docker rm -f pcda_ubuntu

docker pull pcda17/ubuntu-container

docker run --name pcda_ubuntu -ti -p 8889:8889 --volume ~/Desktop/sharedfolder/:/sharedfolder/ pcda17/ubuntu-container bash

In Windows 10, open PowerShell and enter the following to launch the Docker container:

docker rm -f pcda_ubuntu

docker pull pcda17/ubuntu-container

docker run --name pcda_ubuntu -ti -p 8889:8889 --volume C:\Users\***username_here***\Desktop\sharedfolder:/sharedfolder/ pcda17/ubuntu-container bash

And enter the following line to launch the Python shell.

python3

Assign a sentence to the variable sentence — in this case the opening line from John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces. Type the name of the variable and hit return to view your new string.

sentence = "A green hunting cap squeezed the top of a fleshy balloon of a head."

sentence

Output:

A green hunting cap squeezed the top of a fleshy balloon of a head.

We’ll be using lists (which are indicated by brackets []) a lot in the coming weeks. To review Python’s slice notation, we’ll create a variable “words” and assign it a list of strings, then we’ll assign a subset of the list to a new variable. Viewing the new variable “words2”, shows the result.

words = ['A', 'green', 'hunting', 'cap', 'squeezed']

words2 = words[2:4]

words2

The Python shell should print ['hunting', 'cap'], i.e., the subset of the list “words” from index 2 to index 3. An index refers to a position within an ordered list.In general, list_name[start:end], where “start” and “end” are integers, returns a subset of “list-name” from index start to end-1. The “end minus 1” bit may seem odd, but in practice it makes slice notation more readable. The snippet above, for instance, gives us a list containing 2 items, equal to 4-2. And if we want to excerpt the first three items in a list, the following notation will do the trick.

words[:3]

Recall that omitting an index number before or after the colon means you want to include all items on that end of the list. The following returns everything from index 2 to the end of “words”: ['hunting', 'cap', 'squeezed'].

words[2:]

If you want to excerpt the last three entries in a list without counting from the beginning, use a negative number before the colon.

words[-3:]

Likewise, the following will slice off the final 3 items in our list, returning ['A', 'green'].

words[:-3]

To reverse the order of a list, add an extra colon and “-1.”

words[::-1]

It’s important to note that in Python, every string is a list of characters under the hood. We can thus reverse the spelling of a sentence like so.

sentence = "A green hunting cap squeezed the top of a fleshy balloon of a head."

sentence[::-1]

If want to break our sentence into words, we can use the split() function to create a list of substrings with the space character as delimiter.

words = sentence.split(' ')

words

The join() function reverses the process, inserting a chosen string (here, a space) between each item in a list. Note that “sentence2” below is identical to our original “sentence” string.

sentence2 = ' '.join(words)

sentence2

sentence

Quick Exercise

Using the techniques outlined above, reverse the order of words in our sentence and combine them into a single string.

A possible solution:

' '.join(sentence.split(' ')[::-1])

Review Continued

Another useful string function is replace(), which lets us swap out one substring for another.

sentence3 = sentence.replace('hunting','baseball')

sentence3

Finally, note that a number can be represented as one of three data types: integer, float, or string.

sample_int = 35

sample_float = 35.4

sample_string = '35'

sample_int

sample_float

sample_string

We can convert among these formats using the int(), float(), and str() functions. After assigning the values below, enter each variable’s name and be sure you understand the result.

cast_int = int(35.4)

cast_float = float(35)

cast_string = str(35)

cast_int

cast_float

cast_string

A string that includes only numbers and possibly a decimal point — no commas or other characters — can also be cast to the int or float data type.

x = int('75')

y = float('107.5')

x

y

Text I/O in Python

Now we’ll review reading and writing text files from the Python environment. Visit Project Gutenberg or the mirror provided and save the plain text version of Swift’s The Battle of the Books, and other Short Pieces to your /sharedfolder on your desktop. It’s a collection of essays, including a line Toole references in the title A Confederacy of Dunces.

First we’ll assign the file’s pathname to the variable filepath and create the file stream object we’ll use to read its contents. Open the Python shell and enter the following lines.

filepath = "/sharedfolder/pg623.txt"

file = open(filepath, encoding='utf8')

Then we’ll make an empty list called swift_lines and iterate through our file stream using a for loop, adding each line to the list as we go.

swift_lines = []

for line in file:

swift_lines.append(line)

Finally, we’ll close our file stream and view a line from our list.

file.close()

swift_lines[1000]

Output:

'flung by the assistance of so foul a goddess should pollute his fountain,\r\n'

Tip: In macOS you can drag a file from Finder to a Terminal window instead of entering the pathname by hand. If the path contains any spaces, these will be escaped (i.e., preceded by a backslash) in keeping with the conventions of Unix-like interfaces.

Python’s

osmodule, however, doesn’t recognize escaped characters. In order to avoid confusion, it’s probably best to avoid using spaces in filenames. If you are in our Docker Container, you will have to edit the pathname to reflect the /sharedfolder/ directory. For example, instead of this pathname: “/Users/yourname/Desktop/Artists.csv” You would use this pathname: “/sharedfolder/Artists.csv”

Each line ends with \r\n , a carriage return followed by a line feed character, suggesting the file was created in a Windows text editor. As Oualline and Noria discuss in this week’s readings, Unix-like systems generally use \n to indicate newlines, while \r\n is standard in Windows and DOS. To complicate matters, early Apple computers used \r on its own for the same purpose.

Tip: While the term “newline” refers to any character or character combination used to mark the end of a line, when we say “newline character” for the rest of the course we’ll mean

\n(formally called “line feed”) unless otherwise noted.

Our text file from Project Gutenberg is broken into short lines, none longer than 74 characters. Many ASCII text files follow this fixed-width convention, designed to fit the 80-character width of many early PC displays. That display format, in turn, was chosen to work with data from 80-column punch cards, introduced by IBM in the 1920s.

Whether we’re adapting to quirks of history or fixing typing mistakes, we’ll often find it helpful to get rid of whitespace characters (newlines, spaces, tabs) at the beginning and end of a given string. For a string named line, line.strip() will return a copy of the string with all newlines and other whitespace characters removed from either end.

line = swift_lines[1000]

line

line.strip()

Python Text I/O Continued

Closing a file stream with close() when you’re done with it is good style, though it’s not strictly required. If you want to keep your code compliant yet crisp, the following format closes a file stream automatically.

swift_lines = []

with open(filepath, encoding='utf8') as file:

for line in file:

swift_lines.append(line)

Or you can use this command, which does the same in one line.

swift_lines = open(filepath, encoding='utf8').readlines()

Note that calling readlines() creates a list of all lines in a text file, including any newline characters (in this case, \r\n ). Let’s take a look at 5 lines from our list.

swift_lines[100:105]

Output:

["their after-life. In July, 1692, with Sir William Temple's help,\r\n", 'Jonathan Swift commenced M.A. in Oxford, as of Hart Hall. In 1694,\r\n', "Swift's ambition having been thwarted by an offer of a clerkship, of 120\r\n", 'pounds a year, in the Irish Rolls, he broke from Sir William Temple, took\r\n', 'orders, and obtained, through other influence, in January, 1695, the\r\n']

We could easily use a for loop with the strip() function to remove newlines from each string in the list, but the following line does the same in a shorter form. Here open() creates a file stream and read() returns the file’s contents as a single string. Finally, some_text.splitlines() returns a list of lines in the string some_text, removing newline characters along the way. Let’s load the file using splitlines() and compare the results.

swift_lines = open(filepath, encoding='utf8').read().splitlines()

swift_lines[100:105]

Output:

["their after-life. In July, 1692, with Sir William Temple's help,", 'Jonathan Swift commenced M.A. in Oxford, as of Hart Hall. In 1694,', "Swift's ambition having been thwarted by an offer of a clerkship, of 120", 'pounds a year, in the Irish Rolls, he broke from Sir William Temple, took', 'orders, and obtained, through other influence, in January, 1695, the']

If we’d like to convert our list of lines to a block of flowable text, we can use join() to combine all items in the list lines, each separated by a space. Note that we end up losing the paragraph breaks we saw in the original file.

swift_text = ' '.join(swift_lines)

swift_text[10005:10223]

Output:

"Satire is a sort of glass wherein beholders do generally discover everybody's face but their own; which is the chief reason for that kind reception it meets with in the world, and that so very few are offended with it."

Accessing Text Files on the Web

The Python module urllib.request makes grabbing text from the Web as easy as working with local files. Let’s download the first two chapters of A Confederacy of Dunces in plain ASCII format.

from urllib.request import urlopen

url = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/pcda17/pcda-datasets/master/week-02/Toole_A-Confederacy-of-Dunces_Ch1-2.txt"

toole_lines = urlopen(url).read().decode('utf8').splitlines()

Let’s look at the 200th line in the file.

toole_lines[199]

Output:

'Ignatius had himself broken the baseball machine by kicking it.'

Since we’ll be doing a lot of text filtering this semester, you should get used to checking whether a string includes a specified substring. Enter the following lines and press return twice. The first return brings us to a new line and lets us add more indented code if we choose to. The second confirms we’ve finished our conditional statement and runs it.

if "Reilly" in "Ignatius J. Reilly":

print("yes")

To do a case-insensitive substring search, use the lower() function to convert your original string to lowercase. If your search term contains any capital letters, you’ll want to convert it to lowercase as well.

if "reilly" in "Ignatius J. Reilly".lower():

print("yes")

Try creating a simple text filter or two, printing all lines that contain a given substring. Run these examples one at a time, then search for a word of your choice.

for line in toole_lines:

if "orleans" in line.lower():

print(line)

for line in toole_lines:

if "doughnut" in line.lower():

print(line)

While you’re at it, use a for loop to identify the sentence by Jonathan Swift (in swift_lines) that Toole references in his title A Confederacy of Dunces. Try to resist the urge to use ⌘+F in TextWrangler.

Defining Functions

We talked a bit about functions last week, but let’s review. Note that when you define a function in the Python shell, pressing return once will move you to the next line within the function-in-progress. Hit return again to finish the function definition and return to the standard Python shell.

Here is a simple function that multiplies a number (float or int) by itself.

def square(number):

return number * number

square(11)

Note that functions can be nested within one another. The following will call the square function twice.

square(square(11))

We can also create functions that take two or more arguments.

def multiply(x,y):

return x * y

multiply(4,6)

And here’s an example of a function that manipulates string data.

def pluralize(string):

return string + 's'

pluralize("eagle")

Tip: There’s a difference between ending a function with

returnas opposed to

Python is weakly typed, meaning intended data types don’t need to be specified in advance when we create a function. Applying an operation to a value of the wrong type will produce an error.

square("eagle")

pluralize(1960)

Using the str, int, and float functions, we can cast values as string, int, or float data types (when doing so is possible).

def pluralize(string):

print(str(string) + 's')

pluralize(1960)

Generating pseudorandom numbers

It is often useful to generate random numbers or make random selections from a set of data. Note that Python can’t generate a mathematically pure sequence of random values; instead, it creates what are called “pseudorandom” values. Details of the difference are beyond the scope of this course, but when we use the term “random” below we really mean “pseudorandom.”

Import the random module and generate a random float X, where 0 <= X < 1.

import random

random.random()

Return a random integer from 0 to 49.

int(random.random() * 50)

This is equivalent to the following:

random.randint(0,49)

Note that randint is inclusive, so it may output 49, the second argument we passed it.

Quick Assignments

Assign a list of strings to a variable — in this case, a collection of foods mentioned in Toole’s novel.

foods = ['macaroon', 'hot dog', 'jelly doughnut', 'Dr. Nut', 'wine cake', 'Dutch cookies', 'stuffed eggplant', 'jumbalaya with shrimps', 'brownie']

Assignment: Write a function that accepts a list of strings and returns a randomly chosen value.

A possible solution:

def random_choice(list): return list[int(random.random()*len(list))] random_choice(foods)

Assignment: Create a new function that returns a list of 3 randomly chosen strings. Don’t worry about repetitions.

A possible solution:

def random_three(list): temp_list = [] for i in range(3): temp_list.append(random_choice(list)) return temp_list random_three(foods)

Assignment: Modify the function to return a list of 3 random strings containing the letter “a.” Don’t worry about repetitions.

A possible solution:

def random_three_with_a(list): temp_list = [] while(len(temp_list)<3): temp_choice = random_choice(list) if ‘a’ in temp_choice: temp_list.append(temp_choice) return temp_list

random_three_with_a(foods)

As you might expect, Python provides tools to speed up the work you just did by hand. The following returns a single randomly selected item from a list.

random.choice(foods)

This command returns a list of three random selections without repetition.

random.sample(foods,3)

And this one shuffles the order of a list’s contents, overwriting the original list.

random.shuffle(foods)

foods

Random Word

Now let’s choose a random word from the English lexicon. Most Unix-like systems include a standard word list called words, which some programs use (or used to use) for spell checking. Let’s assign the pathname for words to the variable word_path, then load the file as a list of individual words.

words_path = "/usr/share/dict/words"

words = open(words_path).read().splitlines()

Let’s check the length of our lexicon. It should be over 150,000 words.

len(words)

Enter the following to generate a list of 50 random words.

random.sample(words,50)

Is there anything notable about the words in this random list? If so, how might you explain the pattern?

Text Processing Oddities

By this point you’ve likely noticed that text strings can be enclosed in single quotes ('Miss Trixie') or double ("Patrolman Mancuso") at the coder’s discretion.

If we use double quotes, our string can contain single quote characters without ambiguity. Note that the first line below returns an “invalid syntax” error, while the second is successful.

some_text = 'How I'm supposed to know who's a cop? Everybody looks the same to me.'

some_text = "How I'm supposed to know who's a cop? Everybody looks the same to me."

Likewise, single quotes can be used to assign a string containing double quotes.

some_more = '"We goin back to the factory," the spokesman for the choir, the intense lady, said angrily to Ignatius. "You a bad man. I believe a po-lice looking for you."'

To include newline characters and/or any combination of single and double quotes, Python lets us bound strings with triple quotes (i.e., three single quotes in a row). Copy the entire code block below and paste it into the Python shell.

even_more_text = '''"My," Ignatius said to the old man after having taken his first bite. "These are rather strong. What are the ingredients in these?"

"Rubber, cereal, tripe. Who knows? I wouldn't touch one of them myself."

"They're curiously appealing," Ignatius said, clearing his throat. "I thought that the vibrissae about my nostrils detected something unique while I was outside."

Ignatius chewed with a blissful savagery, studying the scar on the man's nose and listening to his whistling.'''

Quick Exercises

Exercise: Download a text file from Project Gutenberg and print 14 randomly chosen lines.

A possible solution:

url = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/pcda17/pcda-datasets/master/week-02/pg623.txt" swift_lines = urlopen(url).read().decode('utf8').splitlines() random_lines = random.sample(swift_lines,14) for line in random_lines: print(line)

Exercise: Modify your code to return 14 random lines containing a chosen word or phrase.

A possible solution:

url = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/pcda17/pcda-datasets/master/week-02/pg623.txt" swift_lines = urlopen(url).read().decode('utf8').splitlines() swift_she = [] for line in swift_lines: if "she" in line.lower(): swift_she.append(line) for line in random.sample(swift_she,14): print(line)

Exercise: Try using a different text and compare the results.

A possible solution:

url = "http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/14328/pg14328.txt" boethius_lines = urlopen(url).read().decode('utf8').splitlines() boethius_she = [] for line in boethius_lines: if "she" in line.lower(): boethius_she.append(line) for line in random.sample(boethius_she,14): print(line)

Launching Jupyter

First, leave the Docker terminal (ctrl+p, then ctrl+q, like we did at the end of last week). Restart the Docker container to run a browser instead of a Terminal applicationso that we can launch Jupyter.

docker rm -f pcda_ubuntu

docker pull pcda17/ubuntu-container

docker run --name pcda_ubuntu -ti -p 8889:8889 --volume ~/Desktop/sharedfolder/:/sharedfolder/ pcda17/ubuntu-container

Windows 10 version:

docker rm -f pcda_ubuntu

docker pull pcda17/ubuntu-container

docker run --name pcda_ubuntu -ti -p 8889:8889 --volume C:\Users\***username_here***\Desktop\sharedfolder:/sharedfolder/ pcda17/ubuntu-container

Open any browser and type (your Juypter Notebook will launch):

localhost:8889

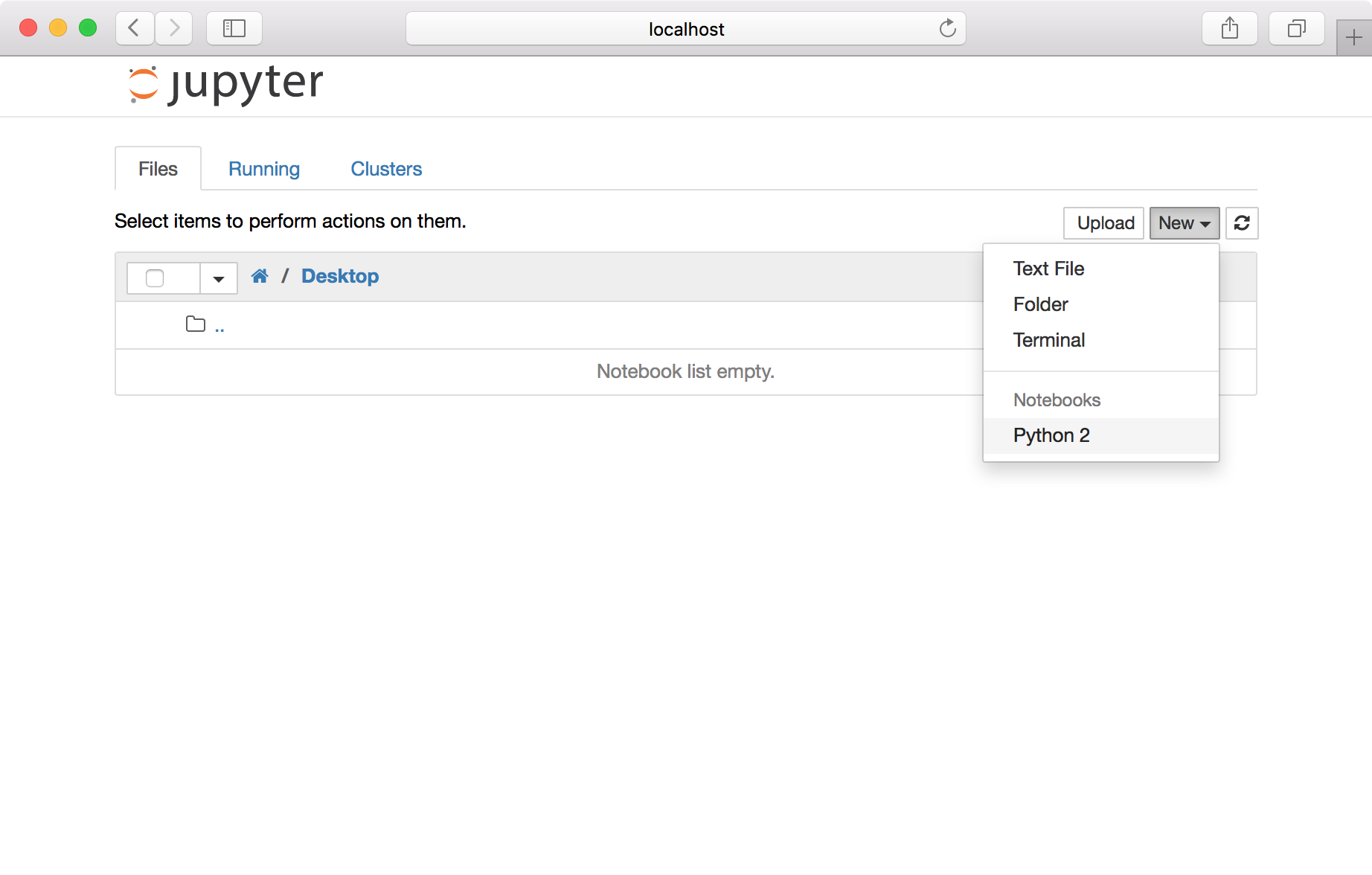

Click the “New” in the upper right, then choose “Python 3” from the drop-down menu.

You’re now in the Jupyter environment. Here, you can create a series of “cells” for individual chunks of code, which can be saved and run repeatedly. Click the ✚ icon on the top left to add a new cell.

Type a line of code that prints a string. To run the current cell, either click the ►❙ icon or go to the “Cell” menu and choose “Run Cells.”

print("Hello Jupyter!")

Note that each cell’s output is displayed right below to the the code that produced it, which is a major benefit of working in Jupyter. We’ll learn more about the Jupyter environment next week. For now, switch back to Terminal.

View list of all installed Python modules

Enter the following command to enter Python’s help shell.

help()

Now enter the following and press return. After a moment, Python will display a list of all available modules.

modules

Enter the name of a module and press return to view its help page, including a list of the module’s functions and other resources.

random

Press q to close the help page, then hit return to get back to the Python shell. You can jump straight to module’s help page by passing its name to the help() function.

help('random')

Or if the module is already imported, you can refer to the module itself.

import random

help(random)

To view a pared-down list of module resources, use the dir() function instead.

dir(random)

The result is a challenge to read through, so let’s introduce the pprint, or “pretty-print” module.

from pprint import pprint

pprint(dir(random))

pprint displays one item from the list per line, a much more readable format. We won’t mention pprint often in these tutorials, but keep it in mind for your own future use.

The os module

The os library contains many useful tools for working with local files and even issuing commands directly to the system shell. We’ll start by importing the os module, navigating to the desktop, and creating a list of the directory’s contents.

import os

os.chdir("/sharedfolder/")

file_list = os.listdir("./")

file_list

The os.system function lets us issue commands at the level of the system shell. The following example will print the contents of your desktop. Note that whereas os.listdir() returns a list object containing filenames, the following simply displays a list of files as if you were using the Bash shell.

os.system("ls /sharedfolder/")

Tip: Spaces in filenames are handled differently in

os.chdir()andos.system(). In the latter case they must be escaped (preceded by a backslash) in keeping with Unix conventions, while in the former escaped spaces will generate errors. For convenience, it’s helpful to avoid spaces in filenames.

Downloading Reviews from Amazon (the hard way)

Start a new Python 3 notebook by going to File/New Notebook in the Jupyter window.

Enter the following in a cell.

from urllib.request import urlopen

url = "http://www.amazon.com/Confederacy-Dunces-John-Kennedy-Toole/dp/0802130208"

page = urlopen(url).read().decode('utf8')

print(page)

To make things simple, let’s chop off the top of the page. Find a piece of text that only appears between the product details and the reviews — “Top customer reviews” is a good example — and use split() to make a list with two elements. Then assign the second chunk (at index 1) to the page variable.

page_bottom = page.split("Top customer reviews")[1]

Now let’s chop off the bottom of the page the same way.

page_middle = page_bottom.split("Set up an Amazon Giveaway")[0]

Next we’ll split the remaining text into individual reviews. Note that the “review rating” HTML class is used at the beginning of each review. We’ll split our page at those points, using triple quotes to include the end of the HTML tag.

review_list = page_middle.split('''review-rating">''')

print(review_list[0])

Since the first item in our list of segments comes before the first review, we’ll remove it using list index notation.

review_list = review_list[1:]

Now the first element of our list should begin with a review.

print(review_list[0])

Now let’s remove the code following each review. Since the text “Was this review helpful to you?” appears after every review, let’s use that as our delimiter. We’ll split each segment at that point and discard everything that follows it using list bracket notation.

review_list_2 = []

for review in review_list:

review_list_2.append(review.split("Was this review helpful to you?")[0])

test_review = review_list_2[0]

print(test_review)

Now that our reviews are roughly cut down to size, let’s clean them up by removing HTML tags. The following function uses Python’s re module for working with regular expressions to replace any text between < and > with a newline. We’ll talk more about regular expressions later in the course.

import re

def strip_html(data):

p = re.compile(r'<.*?>')

return p.sub('\n', data)

Let’s see an HTML-free version of the segment we looked at above.

strip_html(test_review)

Note that there are multiple newlines between fields of interest, each one corresponding to a tag that’s been removed. Since we’d like to create a list of fields, we could use split('\n') to divide the text at each newline character — but then we’d also break up reviews with multiple paragraphs. Instead we’ll use pairs of newlines as our delimiter.

test_review_segments = strip_html(test_review).split('\n\n')

print(test_review_segments)

We’re getting there, but our list contains some empty strings and several entries may begin with newline characters. We can take care of these issues with a for loop, creating a new list that excludes empty strings and applies strip() to remove whitespace from each field we add.

final_review_segments = []

for item in test_review_segments:

if item != '':

final_review_segments.append(item.strip())

print(final_review_segments)

In-Class Exercise

Open your text editor of choice. Drawing on the code examples above, create a script that accepts a URL and produces a list of lists, one for each review on the page. A good strategy is to split the work between two functions: one that accepts a segment of the text and code (such as test_review above) and returns a cleaned-up list of fields, and a second that converts a review and its surrounding code to a list of segments.

You can use the html_stripper() function above or modify it at will.

A possible solution:

from urllib.request import urlopen from pprint import pprint import re def strip_html(data): p = re.compile(r'<.*?>') return p.sub('\n', data) def review_to_list(review): temp_list = strip_html(review).split('\n\n') review_list = [] for item in temp_list: if item != '': review_list.append(item.strip()) return review_list def page_to_table(url): page = urlopen(url).read().decode('utf8') page_bottom = page.split("Top customer reviews")[1] page_middle = page_bottom.split("Set up an Amazon Giveaway")[0] review_list = page_middle.split('''review-rating">''') review_list = review_list[1:-1] review_list_2 = [] for review in review_list: review_list_2.append(review.split("Was this review helpful to you?")[0]) table = [] for review in review_list_2: table.append(review_to_list(review)) return table url = "http://www.amazon.com/Confederacy-Dunces-John-Kennedy-Toole/dp/0802130208" review_table = page_to_table(url) pprint(review_table) import csv outpath = "/sharedfolder/amazon.csv" o = open(outpath, 'w') a = csv.writer(o) a.writerows(review_table) o.close()